Alternate Learning Project

The activism of the 1960s continued into the '70s, particularly for women, other minorities, and environmental causes. It was a time of educational ferment as well. The public schools were rejecting the rigid classroom structure — fixed lessons, standardized testing, and a formalized curriculum — believing that those practices crushed students' creativity. In its stead, they promoted the "open classroom," wall-less settings where children could interact with things and one another at 'interest centers' where they could learn at their own pace and in their own way.

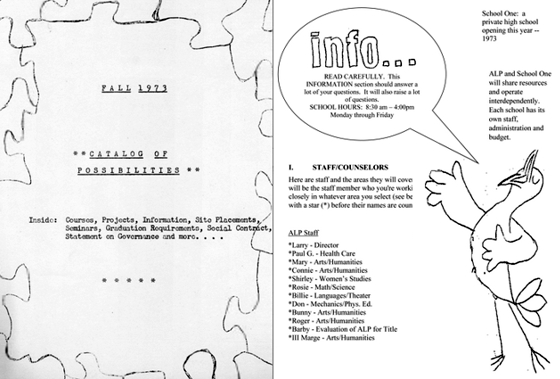

On a national level, Title III of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act provided funding to local groups for demonstration projects which might challenge long standing practices and assumptions about how children learn best — thus bringing much needed change to our schools. One such effort took place in Providence Rhode Island, in a deserted bowling alley, where a small group of educators gathered to build a very different kind of school. It was called the Alternate Learning Project (ALP)

At ALP, students assumed responsibility for their learning and their life. They shaped their program of study; expressed their ideas openly, moved freely about, subject to minimal rules which they themselves helped create.

The school valued not just intellectual intelligence, but social and emotional intelligence as well - underscoring the interplay of all three. Central to ALP was the concept of community - both within and without. "Community within" treated the lives of its students and their interpersonal relationships as legitimate subject matter and a vital part of the learning process. "Community without" meant doing the same between its members and the world at large-the city, its neighborhoods, the state, its institutions and its people, acknowledging and confronting that external social and political reality, incorporating it into the curriculum and the lives of its students.

ALP had little time for the traditional niceties of schooling. Its motif was confrontational pedagogy- direct conversation, testing, and dialogue. Conflict was neither courted nor avoided. When it happened, it was dealt with head-on, mined as a rich source of learning. No crisis was deemed to be without some learning value. Teachers learned together with their students. All grew in the process.

TODAY

School-building and reform are once more at the forefront of our national consciousness. There is an on-going debate over public vs. charter schools, vouchers and privatization, the infusion of large sums of philanthropic money, the best use of the new technology, and the most effective models for learning.

These, however, are mere sub-sets of a larger question which the current dialogue fails to address: What social/moral imperative will inform and shape these efforts : education for what-- towards what end-for what purpose?

We do not offer ALP as the model, but as a model, for the painful, tedious, and complex task of creating a viable educational setting-one which made a conscious effort to seamlessly blend thought, feeling, and action together, while operating in the bowels of the system.

Read the story of ALP; how it came to be; its inner dynamics; interplay with the system; and its relevance today. It's there and much more in "Dancing on the Contradictions. "